DIY Diary: Nathan Carter, Historical Brewer

An English brown ale cools in Nathan Carter’s Uptown apartment, a malty and fullbodied brew that most would be happy to bottle as is. But Carter is a historical brewer, and so he’s following a recipe written by an obscure English nobleman 345 years ago.

After some deciphering of the Enlightenmentera lingo (“sack” refers to fortifi ed wine, for example), Carter turns to the brown ale and drops in dried fruit and spices, a quart of sherry—and one whole chicken.

An early reference to the “cock ale” he’s brewing surfaced in a 1669 cookbook, The Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby. “It was designed as restorative, for strength and vigor,” Carter said. “The chicken was thought to enrich the beer, not unlike chicken soup.”

The strange brew sat for a week in Carter’s fermenter before he strained it off and took a sip. “I got woody, caramel fl avors of the sherry and brown ale, which gave way to spice notes and fruit. And in the very back, savory umami,” he said. “I thought it would be gross and no one would get it, but it works. It’s surprisingly pleasant.”

The cock ale might be Carter’s most offbeat bottling, but he’s long been interested in ancient recipes. His first impulse to ferment came in 2001, during an Old English literature class at Tulane.

“We were reading Beowulf, and they’re sitting in a mead hall drinking mead, and I thought, ‘That sounds awesome. Why don’t we drink mead anymore?’”

Turns out it was easier for him to open a makeshift brewery under his dorm room bed than to find an authentic recipe he could use and adapt. Eventually he revived a formula for medieval mead—written in Middle High German. The translation to English included instructions like “boil the same wort against an acre” (or, boil as long as it takes to walk the length of an acre and back). When he couldn’t figure out the units of measurement, he used ratios.

“It’s tricky, because I’ll only know a recipe works when I taste it,” Carter said. “But it makes less sense to brew something you may as well pick up at the store. I can’t not experiment.”

(In one such test, Carter chewed and spat out cassava root for hours to make a saliva-fermented ale. This method is still practiced globally in regions where “grains aren’t easily maltable,” he said.)

Another challenge was that, for centuries, drinkers were accustomed to warm, aged and flat brews in their pewter tankards. Even “young, live” beers, which carried a natural effervescence, wouldn’t be carbonated enough for today’s taste buds.

“We expect beer to be refrigerated, bubbly and taste of hops,” Carter said. “Certainly some of the murkier, bitter brews of yore wouldn’t sell well in a modern market.”

That doesn’t mean that medieval people, who often turned to beer instead of dicey drinking water, didn’t care about the experience.

“I have no doubt they wanted their ales to taste pleasant, or else they wouldn’t have drank as much as they did,” Carter said. “It’s just that they had different expectations. The palates of ancient people were very different from mine.”

Some old traditions can serve a thoroughly modern purpose. Take Carter’s latest project, a grapefruit golden ale based on malted sorghum. Sorghum has been used in beer for hundreds of years, but today the “alternative” crop has made a comeback, as it produces a beer that’s gluten-free.

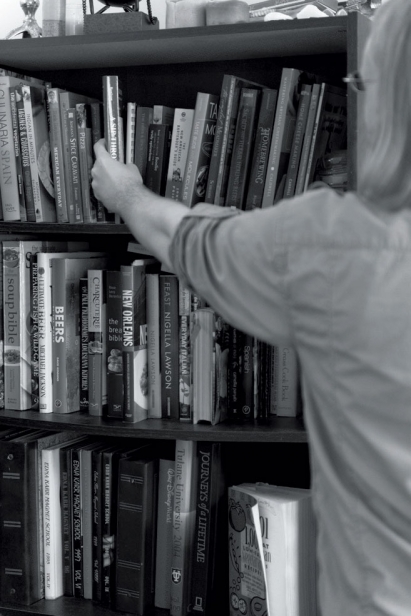

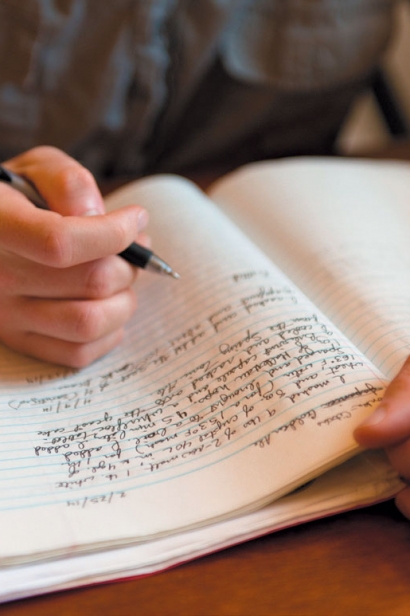

Like Carter’s other brews, the sorghum ale is made in his apartment kitchen and stored in the dining room. Here, capped bottles are stacked in plastic tubs and shadowed by a library of wonky beer books. Among them is a red folder stuffed with hand-copied recipes and tasting notes. (“Quite sharp,” he notes of a steam beer. “Take out the black patent malt.”)

He has no room for kegs, and if he wants the essence of barrel-aged beer, he slips wood chips into the carboy (Tabasco- soaked chips give a peppery bite to strong, malty beers like barleywine).

Bounded also by time (he works for the city) and the sub-tropical season (he won’t brew in the summer, when the air’s “blossoming with microbes”), Carter manages to make about a dozen batches of beer a year, mostly for friends, including the hosts of the Dash & Pony cocktail parties.

Behind the apartment, his strip of a garden, improbably, holds about a dozen tubers, edible weeds, herbs, kale, wood oats and barley, all organic.

Virtually all the compost-fed crops, with the exception of garlic, is fodder for the fermenter. In the past, he’s also harvested sweet potato, which taught him that packing soil around the growing vine can nudge it upwards (when your garden’s two feet wide, you have to go vertical).

He lost last year’s barley to pests and disease, so this time he’s going with a variety native to our region, and hardier.

“I only plant things that want to be here, and that I don’t have to worry about,” he said.

In that sense, he’s found common ground with preindustrial brewers, such as early American settlers who turned to acorn beer when they ran out of barley and hops.

To make his own batch, Carter sourced 10 pounds of acorns from an animal feed store (unprocessed nuts are toxic). Then he spent hours shelling, sorting, soaking, grinding and roasting them.

“That was a process,” Carter said. “But I feel that connection to history. People through the ages use what they have on hand.”

Similarly, his spring tonic ale comes from an old tradition of gathering greens at the first blush of spring. Technically, the ale is an herbal gruit, distinctive for using edible weeds like dandelion or sow thistle, rather than hops, as bittering agents.

To replicate hops’ acidity, Carter also added rhubarb (locally, you can substitute oxalis).

He was pretty faithful to the gruit style with one exception: He had to carbonate.

“I figured the flavor would be enough of an anachronism, without the beer being flat,” Carter said. “I have a lot of respect for the old recipes, but I want to introduce them in a palatable way.”